Nominal-logit model for

McKinney data

In this example we use data from the McKinney Homeless ResearchProject study (Hough, et. al.,

1997; Hurlburt, et. al. 1996) to illustrate the fitting of a nominal

model. For information on specific topics, please use the links below:

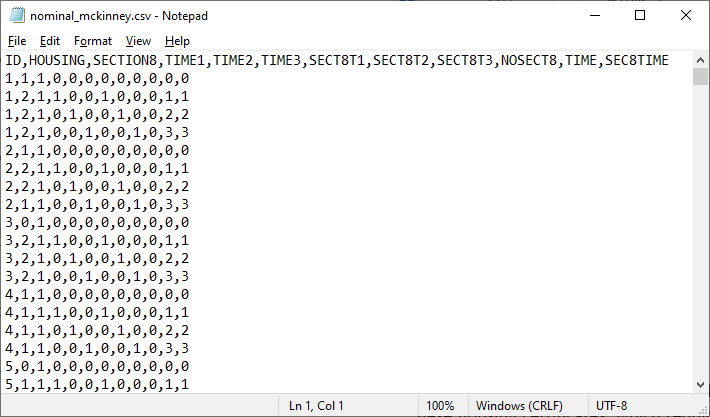

The data

The

McKinney Homeless Research Project study was

designed to evaluate the effectiveness of using Section 8 certificates to

provide independent housing to the severely mentally ill homeless. These

housing certificates, which require clients to pay 30% of their income toward

rent, are meant to enable low-income subjects to choose and obtain independent

housing in the community. Three hundred sixty-two clients took part in this

longitudinal study employing a randomized factorial design. Clients were

randomly assigned to one of two types of case management (comprehensive vs.

traditional) and to one of two levels of access to independent housing (using

Section 8 certificates). The project was restricted to clients diagnosed with a

severe and persistent mental illness who were either homeless or at high risk of becoming homeless

at the start of the study. Individuals' housing status was classified at

baseline and at 6-, 12-, and 24-month follow-ups. Here, we focus on examining

the effect of access to Section 8 certificates on housing outcomes across time.

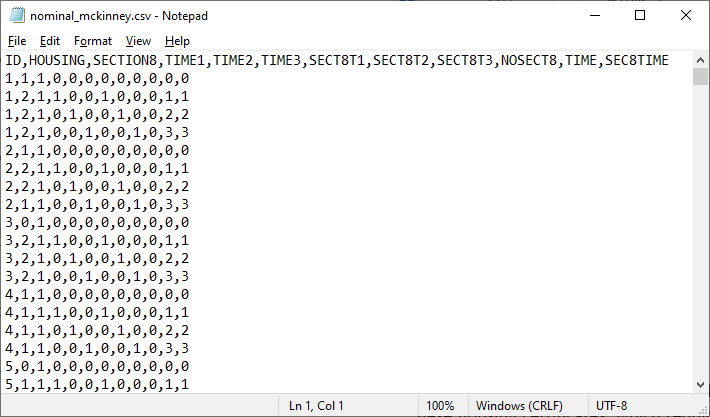

At each time point, subjects' housing status was classified as either

streets/shelters, community housing, or independent housing; a partial list of

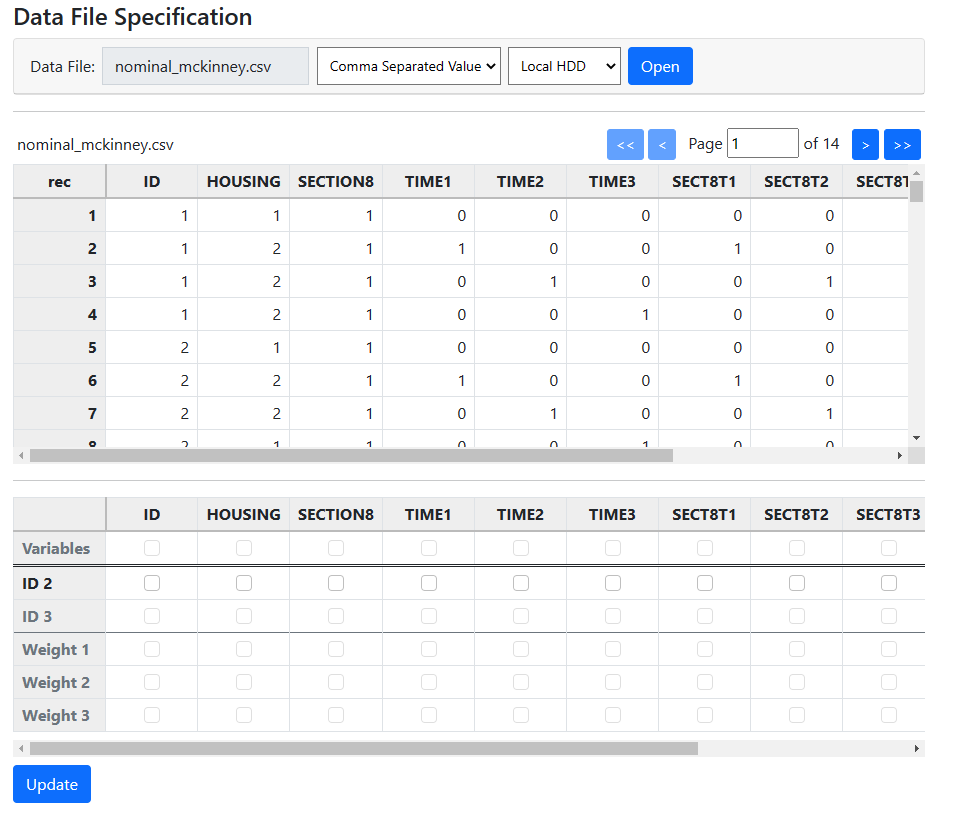

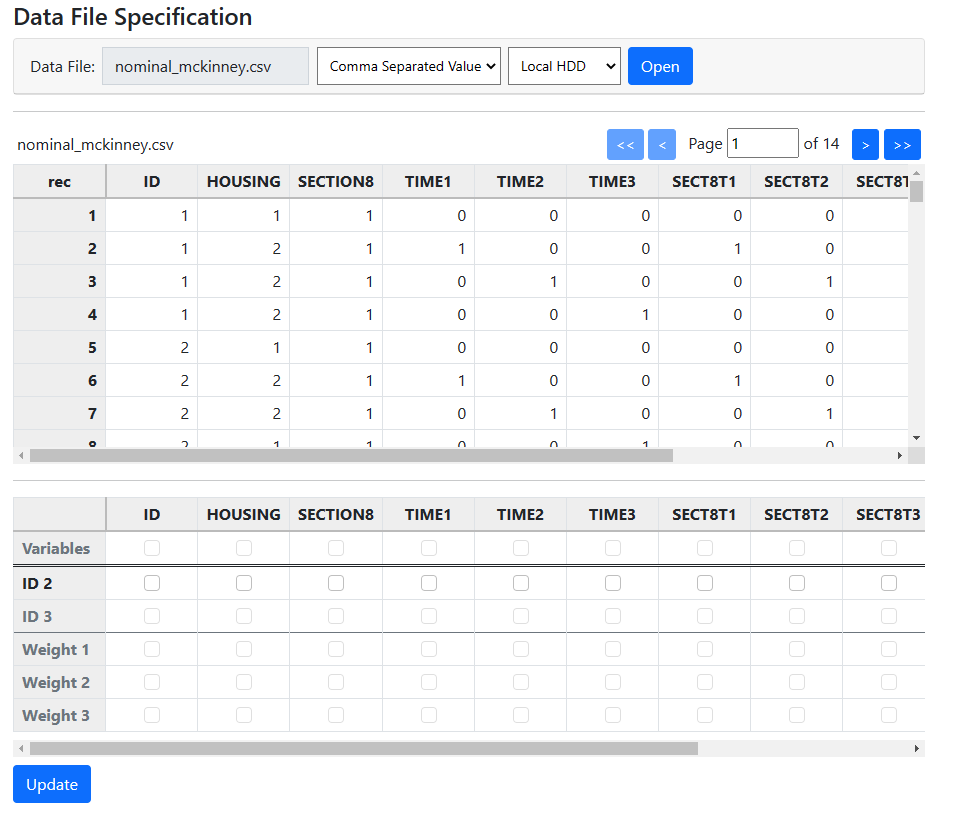

these data is given below in the form of a comma separated values (CSV) file, named

nominal_mckinney.csv.

-

ID is the subject ID (362 subjects in total).

-

HOUSING represents the housing status at

the time of interview: 0 = street, 1 = community, 2 = independent.

-

SECTION8 indicates the Section 8 group,

with 1 representing those using Section 8 certifications, and 0 those without.

-

TIME1 to TIME3 are three dummy variables for time

effects, and denote whether a classification was at baseline, or at the 6-, 12-

or 24-month follow-up. If at the 6 months follow-up, TIME1 = 1 and TIME2 = TIME3 =0;

if at 12 months, TIME2 = 1 while TIME1 = TIME3 = 0; and at the 24-month

follow-up TIME3 = 1 and TIME1 = TIME2 = 0. With this coding scheme, the baseline serves as the reference

group of classification. The coding structure is shown in the table below.

-

Three Section 8 by time interaction terms follow: SECT8T1 is the product of SECTION8 and TIME1, and SECT8T2

and SECTION8 the products of SECTION8 and TIME2 and TIME3 respectively.

-

NOSECT8 indicates the non-Section 8 group, with 0 = no, and 1 = yes.

-

TIME represents the linear time contrast. At baseline, TIME = 0,

at 6 months, TIME = 1, at 12 months TIME = 2, and at 24 months TIME = 3.

-

SEC8TIME is the product of SECTION8 and TIME.

Coding of the dummy variables TIME1, TIME2, and TIME3

| TIME1 | TIME2 | TIME3 | TIME

| baseline | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 months | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 12 months | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| 24 months | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

There are missing data for the housing

status variable. Thus, some subjects are measured at all four time points and

others at fewer time points. Data from these time points with missing values

are not used in the analysis; however, data are used from other time points

where there are no missing data. Thus, for inclusion into the analysis, a

subject's data (both the dependent variable and all explanatory variables used

in a particular analysis) at a specific time point must be complete. The number

of repeated observations per subject depends on the number of time points for

which there are non-missing data for that subject. The correct way to specify

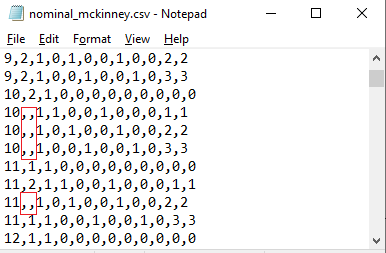

missing data is to enter no value into the CSV file.

The CSV file should contain “,,” instead, as shown below.

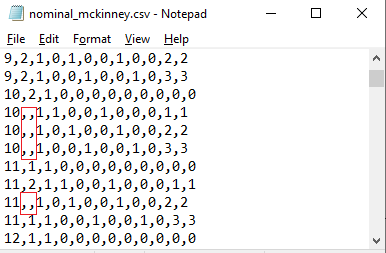

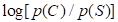

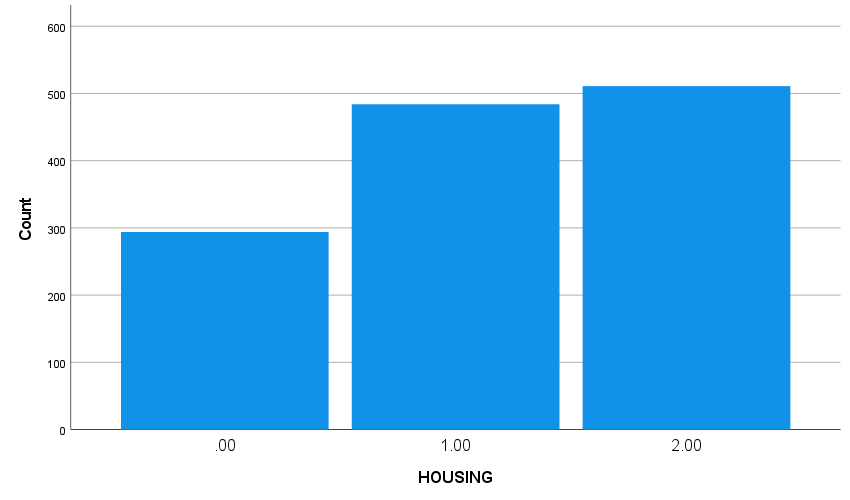

A bar chart of the variable HOUSING is given below. Housing status at

the beginning of the study was mostly independent or in community housing. As

we would like to compare these categories to the “street” category,

we will be using the first category of HOUSING as reference category in the

analysis to follow.

A bar chart of the variable HOUSING is given below. Housing status at

the beginning of the study was mostly independent or in community housing. As

we would like to compare these categories to the “street” category,

we will be using the first category of HOUSING as reference category in the

analysis to follow.

The observed sample sizes and response proportions by group are given in the table

below. These observed proportions indicate a general decrease in street living

and an increase in independent living across time for both groups. The increase

in independent housing, however, appears to occur sooner for the section 8

group relative to the control group. Regarding community living, across time

there is an increase for the control group and a decrease for the section 8

group.

Regarding missing data, further inspection of indicates that there is some attrition

across time; attrition rates of 19.4% and 12.7% are observed at the final time

point for the control and section 8 groups, respectively. In addition, one

subject provided no housing data at any of the four measurement time points.

Since estimation of model parameters is based on a full-likelihood approach,

missing data are assumed to be "ignorable" conditional on both the

explanatory variables and observed nominal responses (Laird, 1988). In

longitudinal studies, ignorable nonresponse falls under Rubin's (1976)

"missing at random" (MAR) assumption, in which the missingness

depends only on observed data. In what follows, since the focus is on

describing use of the nominal model, we will make the MAR assumption (e.g., a

mixed-effects pattern-mixture model as described in Hedeker & Gibbons

(1997)) could be used.

Observed sample sizes and response proportions by group

The observed sample sizes and response proportions by group are given in the table

below. These observed proportions indicate a general decrease in street living

and an increase in independent living across time for both groups. The increase

in independent housing, however, appears to occur sooner for the section 8

group relative to the control group. Regarding community living, across time

there is an increase for the control group and a decrease for the section 8

group.

Regarding missing data, further inspection of indicates that there is some attrition

across time; attrition rates of 19.4% and 12.7% are observed at the final time

point for the control and section 8 groups, respectively. In addition, one

subject provided no housing data at any of the four measurement time points.

Since estimation of model parameters is based on a full-likelihood approach,

missing data are assumed to be "ignorable" conditional on both the

explanatory variables and observed nominal responses (Laird, 1988). In

longitudinal studies, ignorable nonresponse falls under Rubin's (1976)

"missing at random" (MAR) assumption, in which the missingness

depends only on observed data. In what follows, since the focus is on

describing use of the nominal model, we will make the MAR assumption (e.g., a

mixed-effects pattern-mixture model as described in Hedeker & Gibbons

(1997)) could be used.

Observed sample sizes and response proportions by group

| Time point |

| Group | Status | Baseline | 6 months | 12 months | 24 months |

| Control | Street | 0.555 | 0.186 | 0.089 | 0.124 |

| Community | 0.339 | 0.578 | 0.582 | 0.455 |

| Independent | 0.106 | 0.236 | 0.329 | 0.421 |

| n | 180 | 161 | 146 | 145 |

| Section 8 | Street | 0.442 | 0.093 | 0.121 | 0.120 |

| Community | 0.414 | 0.280 | 0.146 | 0.228 |

| Independent | 0.144 | 0.627 | 0.732 | 0.652 |

| n | 181 | 161 | 157 | 158 |

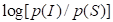

In preparation for the subsequent analyses, the marginal response proportions can be converted to

the two logits of the nominal regression model (i.e.,  and

and  ,

where S = street, C = community, and I = independent housing).

These logits are given below.

Logits across time by group

,

where S = street, C = community, and I = independent housing).

These logits are given below.

Logits across time by group

| Time point |

| Group | Status | Baseline | 6 months | 12 months | 24 months |

| Control | Community vs. Street | -0.49 | 1.13 | 1.88 | 0.130 |

| Independent vs. Street | -1.66 | 0.24 | 1.31 | 1.22 |

| Time point |

| Section 8 | Status | Baseline | 6 months | 12 months | 24 months |

| Control | Community vs. Street | -0.07 | 1.10 | 0.19 | 0.64 |

| Independent vs. Street | -1.12 | 1.91 | 1.0 | 1.69 |

| Difference | Status | Baseline | 6 months | 12 months | 24 months |

| Control | Community vs. Street | 0.42 | -0.03 | -1.69 | -0.66 |

| Independent vs. Street | 0.54 | 1.67 | 0.49 | 0.47 |

The logits clearly show the increase in community and independent housing, relative

to street housing, at all follow-up time points (6, 12, and 24 months). In terms

of group-related differences, these appear most pronounced at 6 months for

independent housing and 12 months for community housing. While examination of

these logits is instructive, the subsequent analyses will more rigorously

assess the degree to which these logits vary by time and group.

In this example, one random subject effect (i.e., a random subject

intercept) is assumed and the repeated housing status classifications is

modeled in terms of the dummy-coded time effects (6, 12,

and 24 month follow-ups compared to baseline), a group effect (section 8 versus

control), and group by time interaction terms.

The model

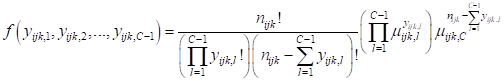

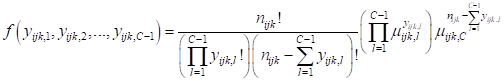

The nominal model is part of a family of models based on the

multinomial distribution, which is a generalization of the Binomial

distribution. It is commonly used in to describe the probability of the outcome

of n independent trials each of which leads to

a success for one of c categories, with each category having a given

fixed probability of success. A nominal variable has categories that cannot be

ordered.

where C represents the number of categories of the

outcome variable.

For the nominal model, the logistic link function is

specified.

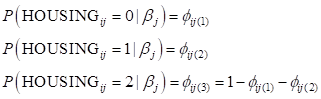

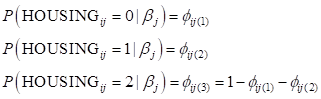

In the current example, the outcome variable HOUSING

is coded 0, 1, and 2. Therefore

where C represents the number of categories of the

outcome variable.

For the nominal model, the logistic link function is

specified.

In the current example, the outcome variable HOUSING

is coded 0, 1, and 2. Therefore

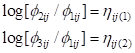

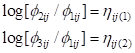

As we wish to use the “street” category as

reference category, we select the first category as reference category and will

thus be considering the two logits

As we wish to use the “street” category as

reference category, we select the first category as reference category and will

thus be considering the two logits

For c = 2 (community housing)

For c = 2 (community housing)

and for c = 3

and for c = 3

.

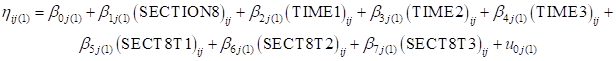

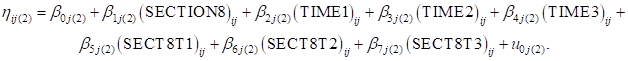

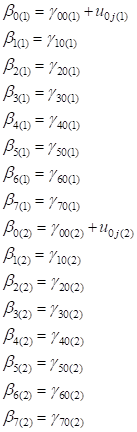

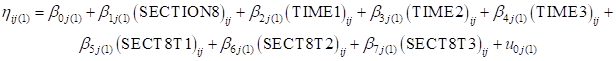

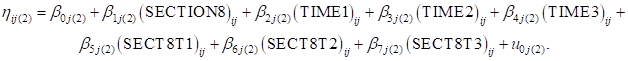

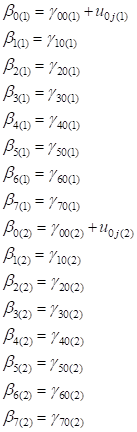

The level-2 model is

.

The level-2 model is

Reading in the data

To construct this model, we select New Analysis on the landing page.

thereby opening the Data page. Select the CSV file and click Open to

obtain the page below.

thereby opening the Data page. Select the CSV file and click Open to

obtain the page below.

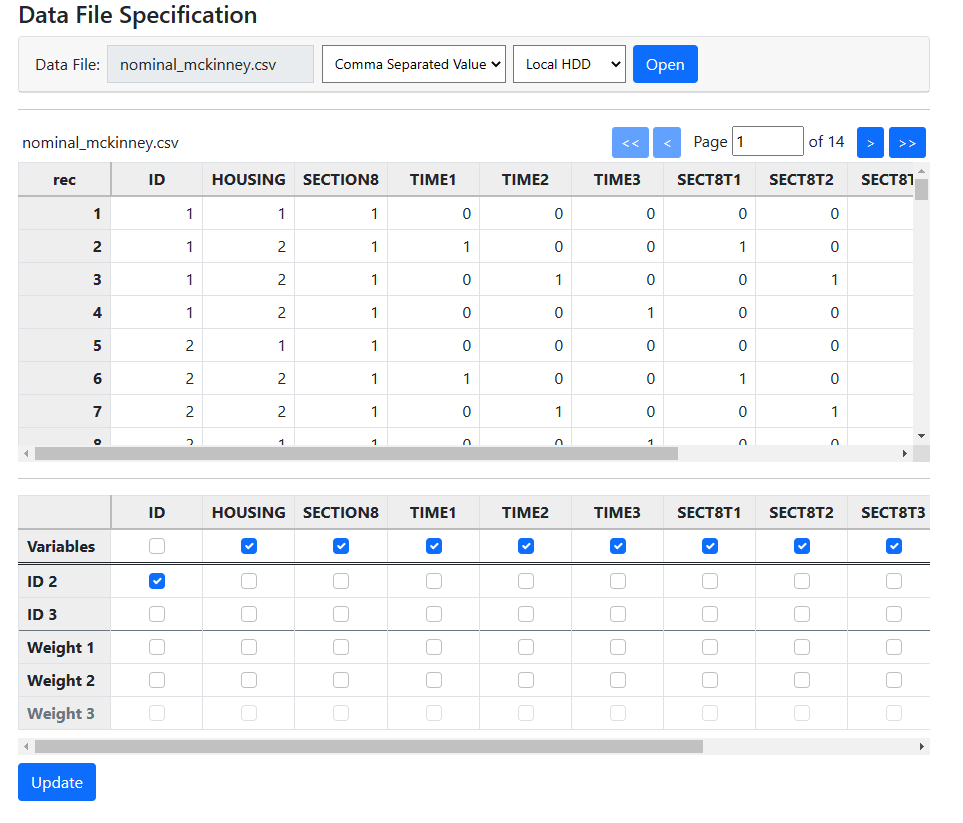

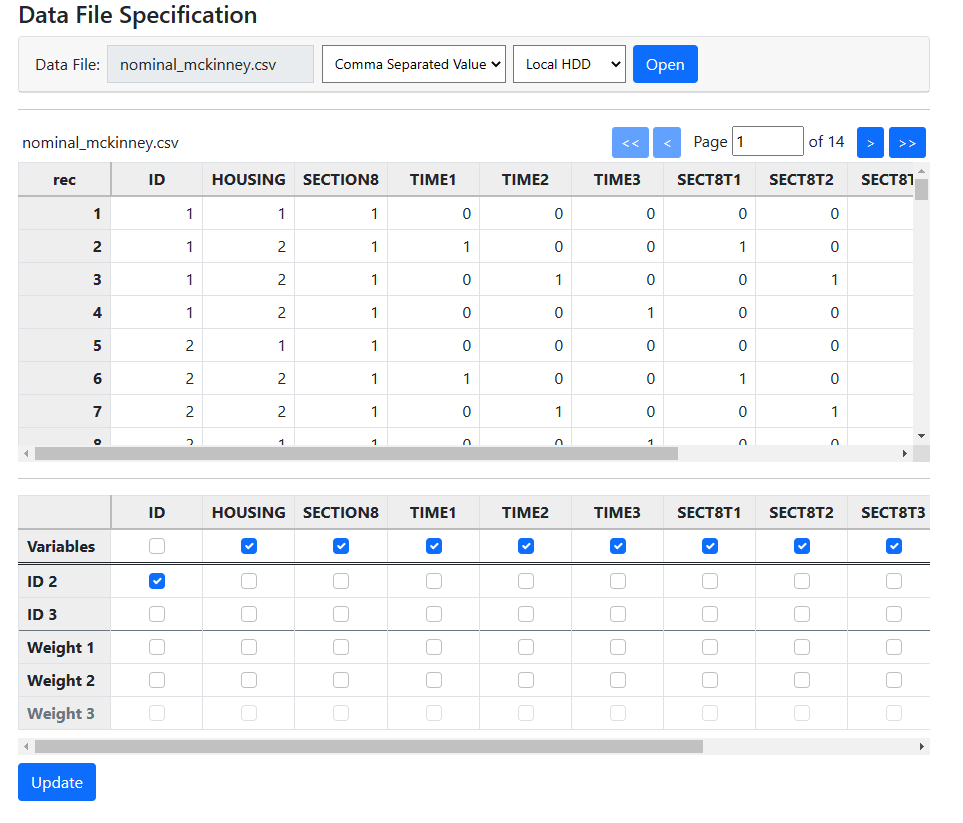

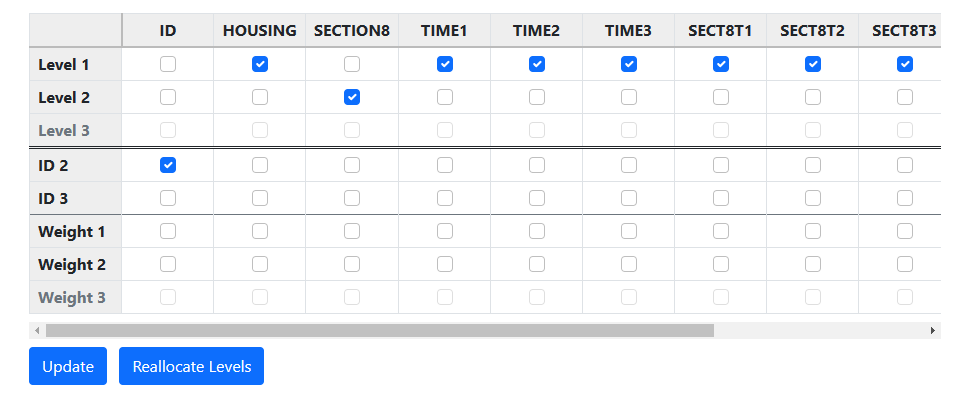

The first step is to select an ID variable. In this case, the variable ID defines

the hierarchical structure, and we select it by checking the box associated

with this variable in the ID 2 line. To select predictors, the boxes in

the Variables line must be checked. We opt to select them all

The first step is to select an ID variable. In this case, the variable ID defines

the hierarchical structure, and we select it by checking the box associated

with this variable in the ID 2 line. To select predictors, the boxes in

the Variables line must be checked. We opt to select them all

before clicking Update. Once Update is clicked the program automatically

determines the appropriate levels of all selected variables.

before clicking Update. Once Update is clicked the program automatically

determines the appropriate levels of all selected variables.

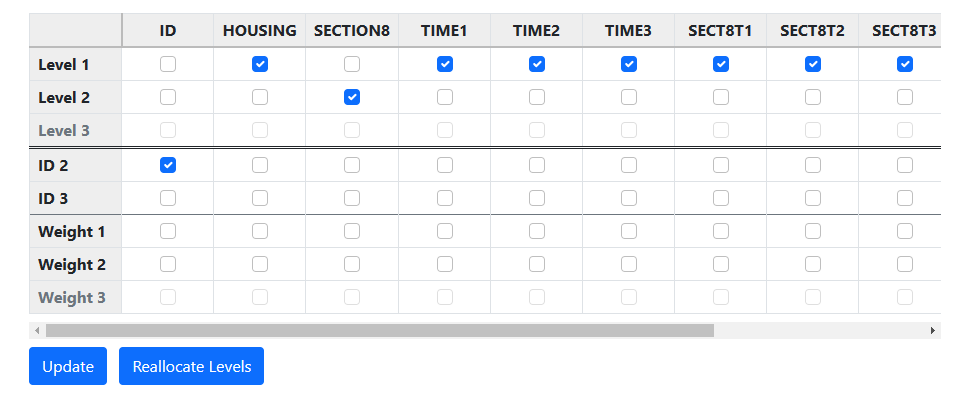

With data specification now complete, model building can begin. Click on Models

at the top of the page to move to the Models page.

With data specification now complete, model building can begin. Click on Models

at the top of the page to move to the Models page.

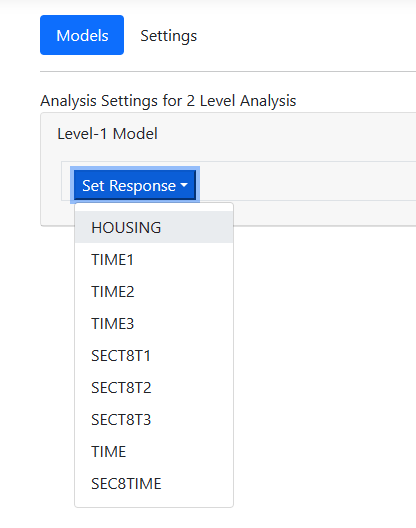

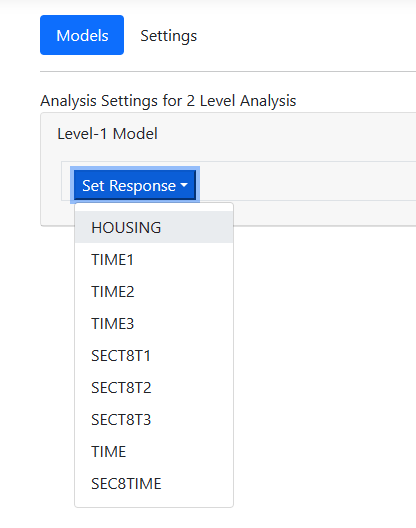

Building the model

The first step is specifying the response variable. Select HOUSING from the

drop-down list associated with the Set Response field. An unconditional

model is now displayed.

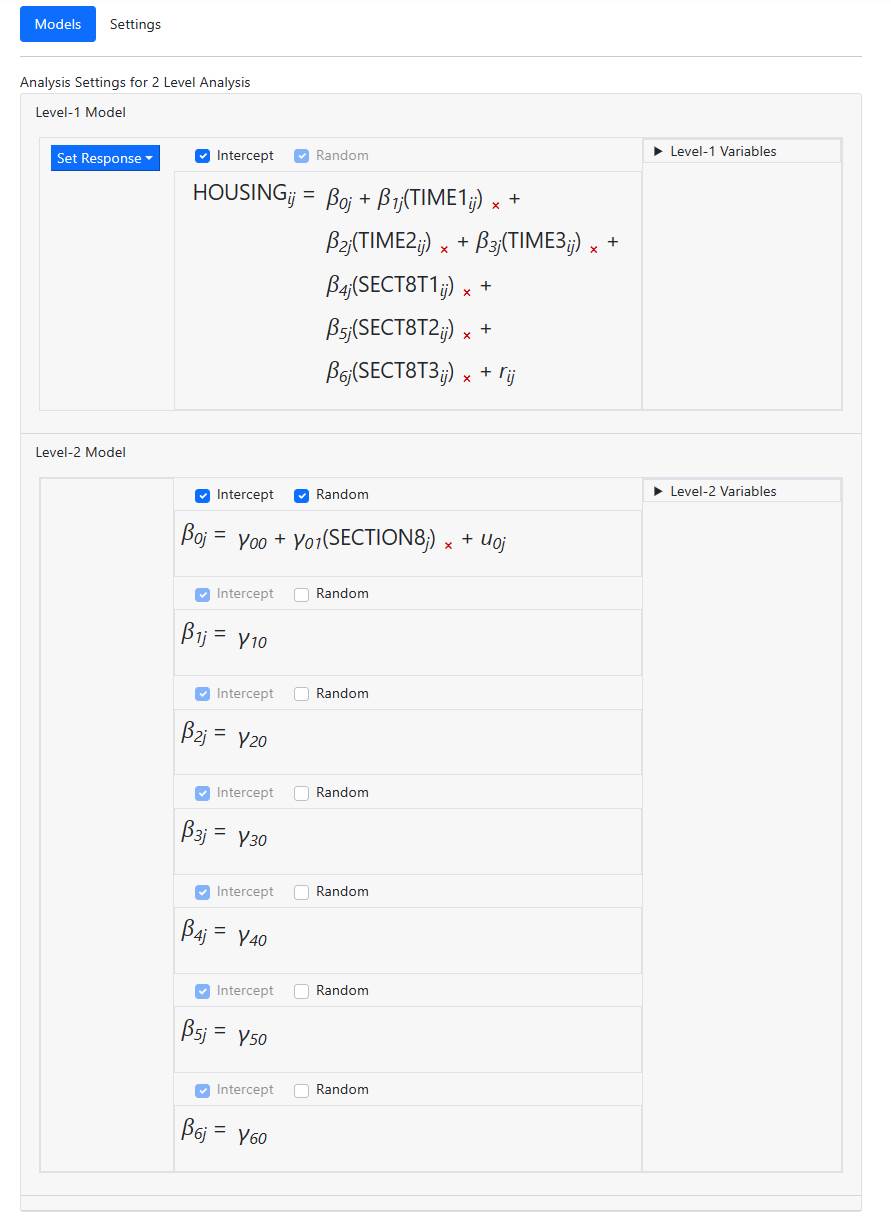

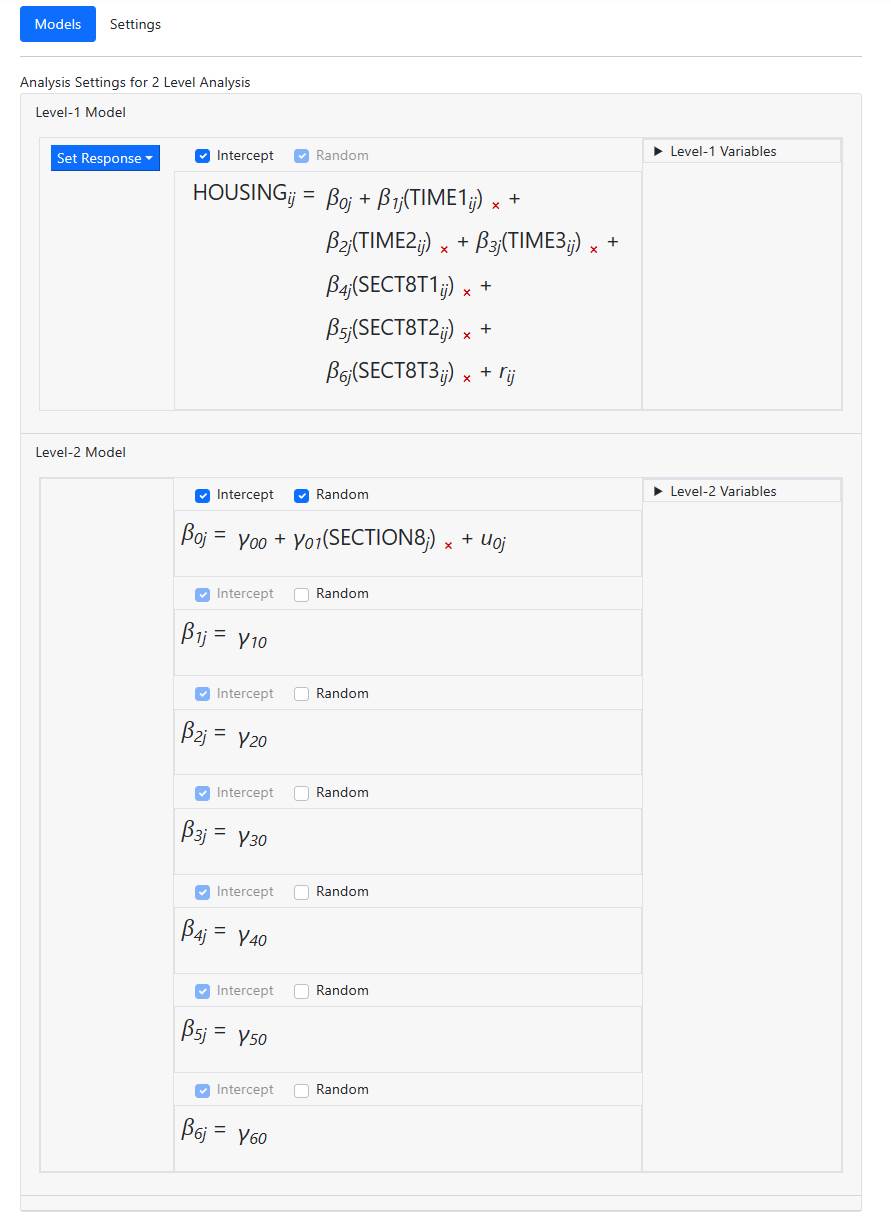

The TIME variables are selected from the Level-1 Variables field by holding

down the Control button while clicking on the names. Next, drag them all

into the level-1 equation before releasing the mouse button. The following

level-1 model appears:

The TIME variables are selected from the Level-1 Variables field by holding

down the Control button while clicking on the names. Next, drag them all

into the level-1 equation before releasing the mouse button. The following

level-1 model appears:

Add the three SECTION8 variables (SECT8T1, SECT8T2 and SECT8T3) in the same way to

the level-1 equation. Then add the variable SECTION8 to the intercept equation

at level-2 to obtain the final model

Add the three SECTION8 variables (SECT8T1, SECT8T2 and SECT8T3) in the same way to

the level-1 equation. Then add the variable SECTION8 to the intercept equation

at level-2 to obtain the final model

Specification

of outcome type and associated options

Move to the Settings page by clicking on Settings at the top of the

page. When the page opens, we see that the programs has correctly suggested a

nominal model as appropriate for these data. The default values of reference

category and link function for the nominal distribution are displayed.

As these settings are exactly what we intend to use, we need not make additional

changes here. We can proceed to run the analysis.

As these settings are exactly what we intend to use, we need not make additional

changes here. We can proceed to run the analysis.

Running the model

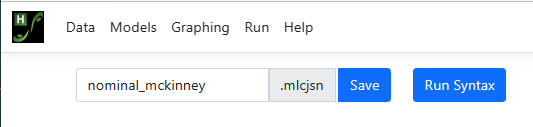

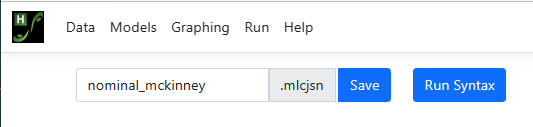

Run the model by going to the Run page by clicking on the Run link at

the top of the page. The Run page opens, and two options are available:

One can Save the model information to a syntax file with file extension

MLCJSN for potential reuse. By default, the default file name assigned

corresponds to the file name of the data file. Using this option is optional,

however, and one can simply click the Run Syntax option to start the

analysis.

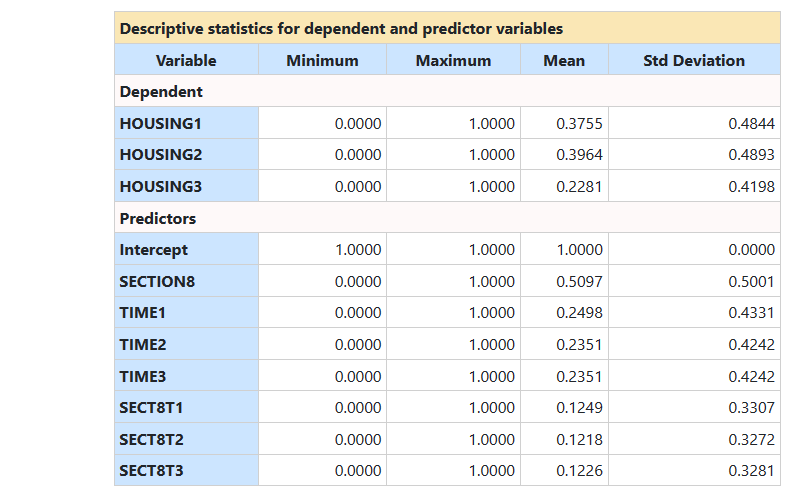

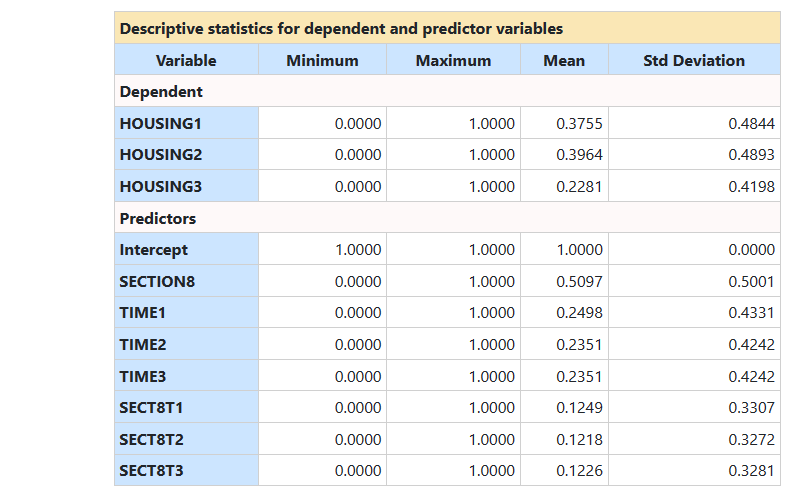

Portions of the output file are shown below. The first

part of the output file gives a description of the model specifications. This is followed by

descriptive statistics for all the variables included in the model. We note that the

most frequent response was in category 2, i.e. "Independent"

on the nominal outcome HOUSING, while 23% indicated

that they were living on the street (HOUSING = 0, the reference category here

represented by the indicator variable HOUSING3). The variable HOUSING1 represents the

respondents living in community housing.

Note that the order of the indicator variables for HOUSING is the opposite of the original coding of the variable: as we selected the

first category as reference category, the program automatically recodes it to

make the selected reference category the last category in the working data set.

One can Save the model information to a syntax file with file extension

MLCJSN for potential reuse. By default, the default file name assigned

corresponds to the file name of the data file. Using this option is optional,

however, and one can simply click the Run Syntax option to start the

analysis.

Portions of the output file are shown below. The first

part of the output file gives a description of the model specifications. This is followed by

descriptive statistics for all the variables included in the model. We note that the

most frequent response was in category 2, i.e. "Independent"

on the nominal outcome HOUSING, while 23% indicated

that they were living on the street (HOUSING = 0, the reference category here

represented by the indicator variable HOUSING3). The variable HOUSING1 represents the

respondents living in community housing.

Note that the order of the indicator variables for HOUSING is the opposite of the original coding of the variable: as we selected the

first category as reference category, the program automatically recodes it to

make the selected reference category the last category in the working data set.

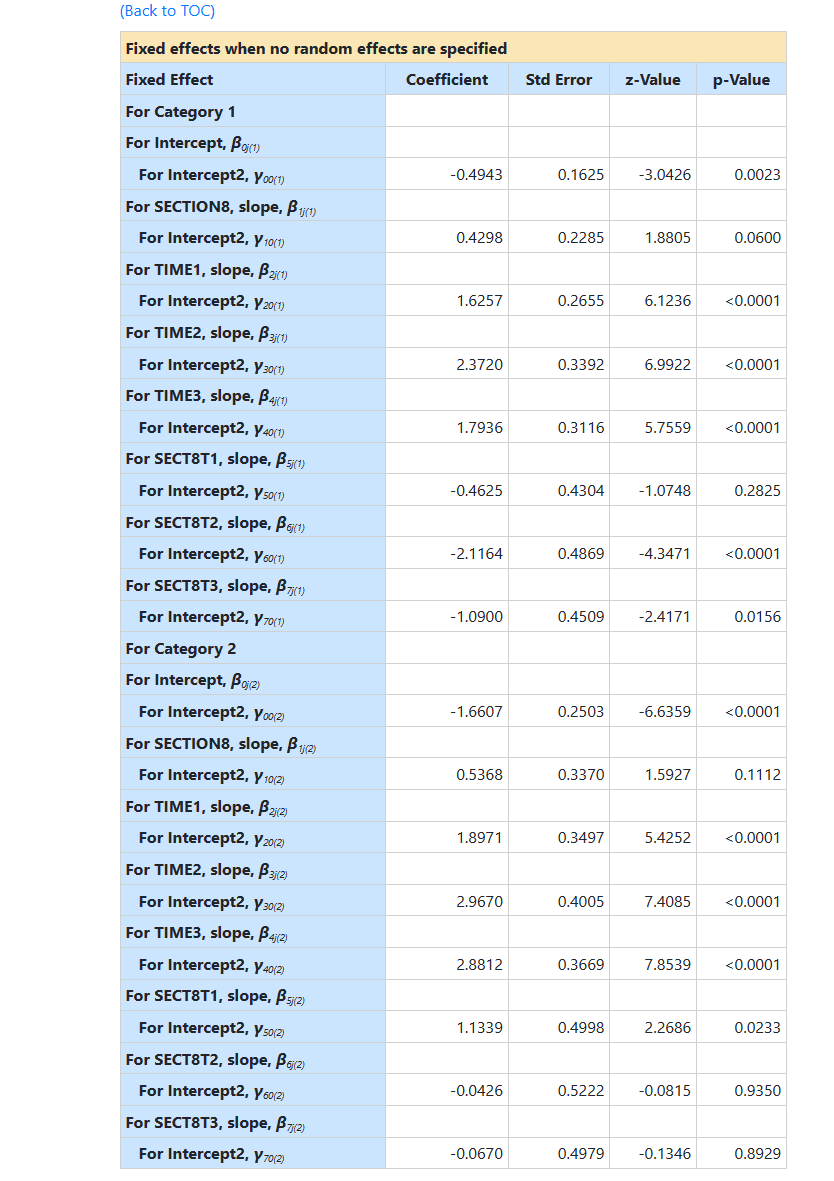

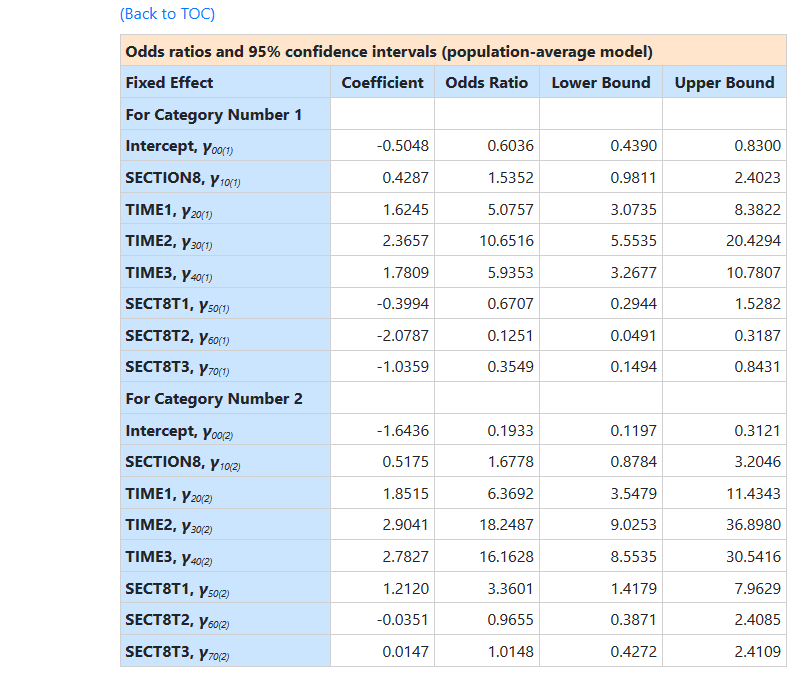

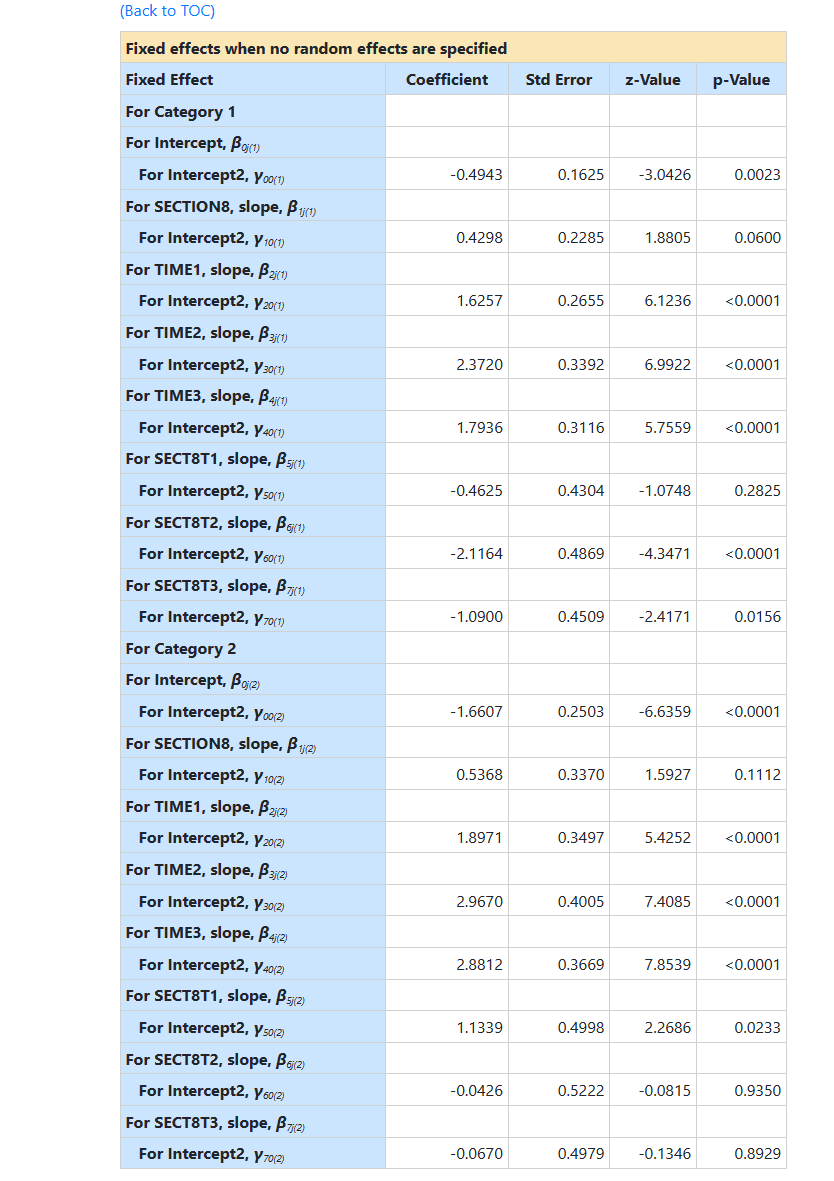

Results for the model without any random effects are

given next. The first eight values are those for the intercept, SECTION8, TIME1,

…, SECT8T3 for response code 1 vs. code 0, the last eight are for the same predictors, but

for response code 2 vs. response code 0.

Results for the model without any random effects are

given next. The first eight values are those for the intercept, SECTION8, TIME1,

…, SECT8T3 for response code 1 vs. code 0, the last eight are for the same predictors, but

for response code 2 vs. response code 0.

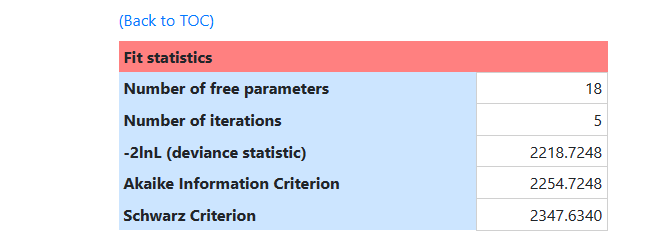

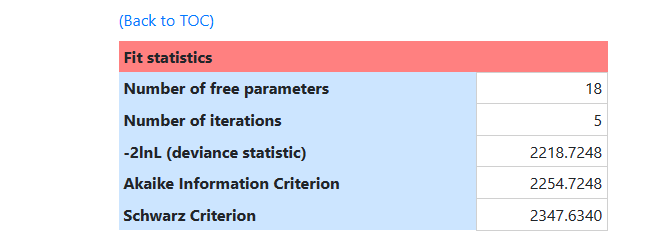

The results obtained with adaptive quadrature estimation are given next.

The results obtained with adaptive quadrature estimation are given next.

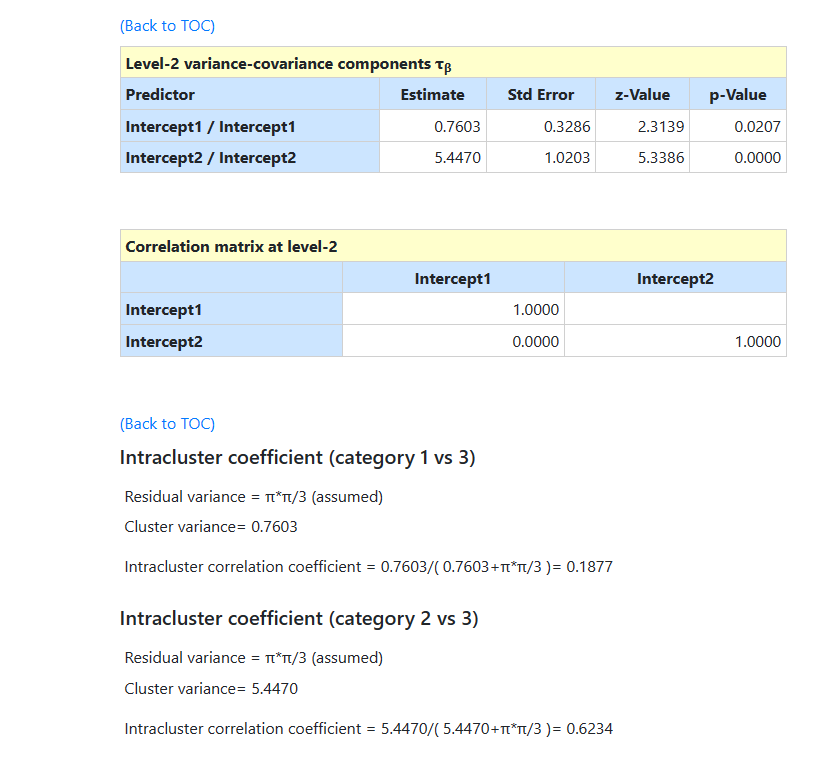

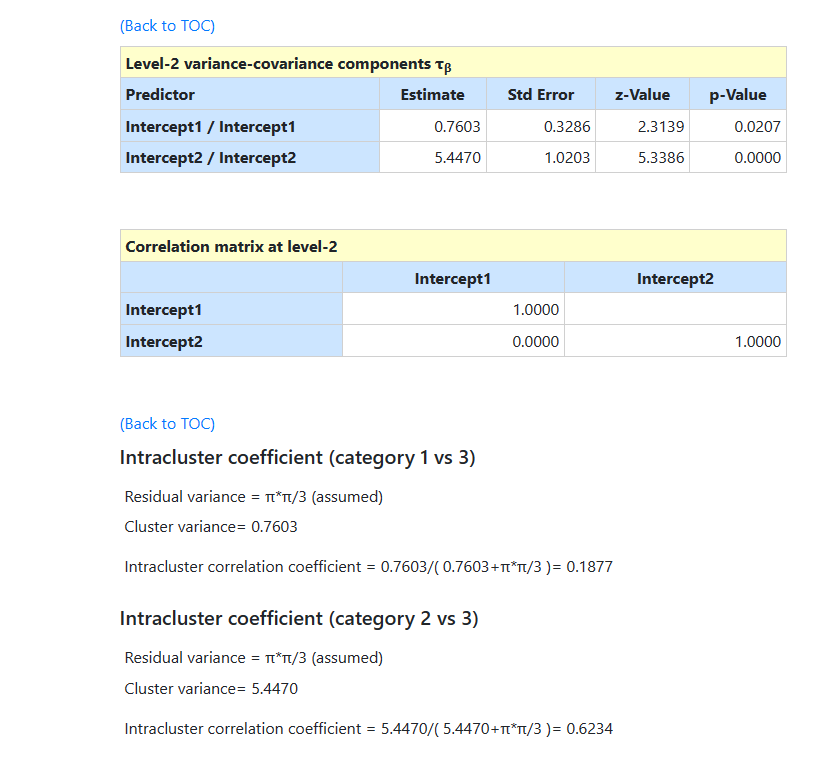

Comparing the log-likelihood value from this analysis to one where there are

no random effects clearly supports inclusion of the random subject effect

(likelihood ratio

Comparing the log-likelihood value from this analysis to one where there are

no random effects clearly supports inclusion of the random subject effect

(likelihood ratio  ). Expressed as intraclass correlations

). Expressed as intraclass correlations

and

and  for community versus street and independent versus street, respectively. Thus, the subject

influence is much more pronounced in terms of distinguishing independent versus

street living, relative to community versus street living. This is borne out by

contrasting models with separate versus a common random-effect variance across

the two category contrasts (not shown) which yields a highly significant

likelihood ratio

for community versus street and independent versus street, respectively. Thus, the subject

influence is much more pronounced in terms of distinguishing independent versus

street living, relative to community versus street living. This is borne out by

contrasting models with separate versus a common random-effect variance across

the two category contrasts (not shown) which yields a highly significant

likelihood ratio  favoring the

model with separate variance terms.

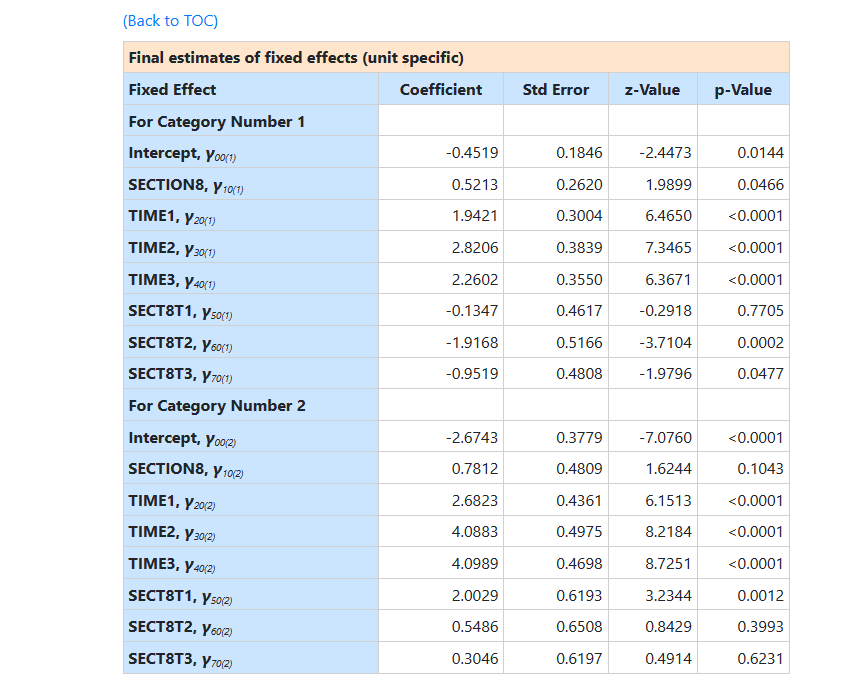

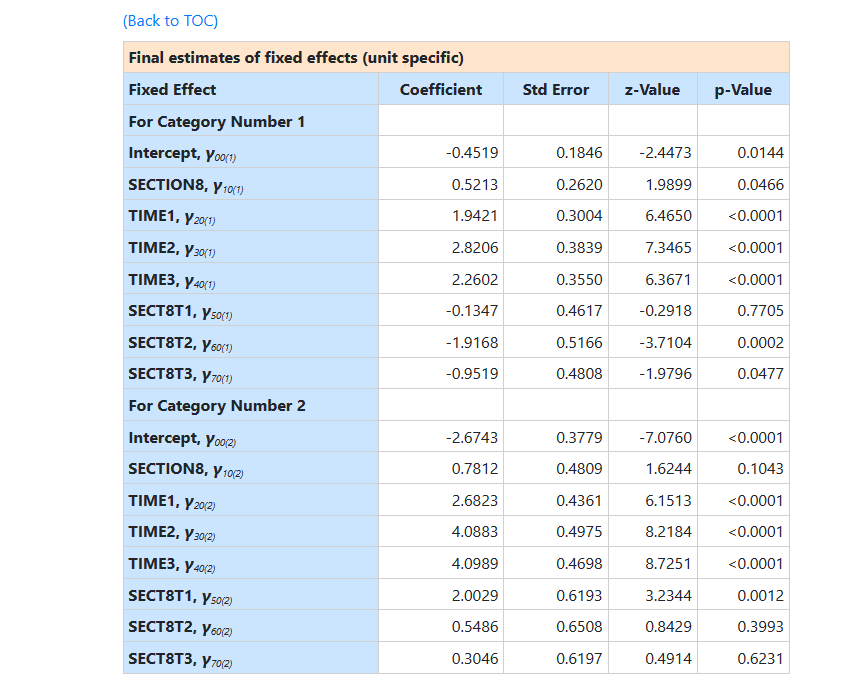

The unit specific results follow.

favoring the

model with separate variance terms.

The unit specific results follow.

In terms of significance of the fixed effects, the time effects

are observed to be highly significant. With the inclusion of the Time by

Section 8 interaction terms, the time effects reflect

comparisons between time points for the control group (i.e., SECTION8

coded as 0). Thus, subjects in the control group show increased use of both

independent and community housing relative to street housing at all three

follow-ups, as compared to baseline. Similarly, due to the inclusion of the

interaction terms, the Section 8 effect is the group difference at baseline (i.e.,

when all time effects are 0). Using a .05 cutoff, there is no statistical

evidence of group differences at baseline. Turning to the interaction terms,

these indicate how the two groups differ in terms of comparisons between time

points. Compared to controls, the increase in community versus street housing

is less pronounced for section 8 subjects at 12 months (the estimate for

SECT8T2 equals –1.92 in terms of the logit), but not statistically

different at 6 months (SECT8T1) and only marginally

different at 24 months (SECT8T3). Conversely, as compared to controls, the increase in independent versus street

housing (response code 2 vs. code 0) is more pronounced for section 8 subjects at

6 months (the estimate equals 2.00 in terms of the logit), but not

statistically different at 12 or 24 months.

In terms of community versus street housing (i.e.,

response code 1 versus 0), there is an increase across time for the control

group relative to the Section 8 group. As the statistical test indicated, these

groups differ most at 12 months. For the independent versus street housing

comparison (i.e., response code 2 versus 0) there is a beneficial effect

of Section 8 certificates at 6 months. Thereafter, the non-significant

interaction terms indicate that the control group

catches up to some degree. Considering these results of the mixed-effects

analysis, it is seen that both groups reduce the degree of street housing but

do so in somewhat different ways. The control group subjects are shifted more

towards community housing, whereas Section 8 subjects are more quickly shifted

towards independent housing.

This differential effect of Section 8 certificates over time

is completely missed if one simply analyzes the outcome variable as a binary

indicator of street versus non-street housing (i.e., collapsing

community and independent housing categories). In this case (not shown), none

of the section 8 by time interaction terms are observed to be statistically

significant. Thus, analysis of the three-category nominal outcome is important in uncovering the beneficial

effect of Section 8 certificates.

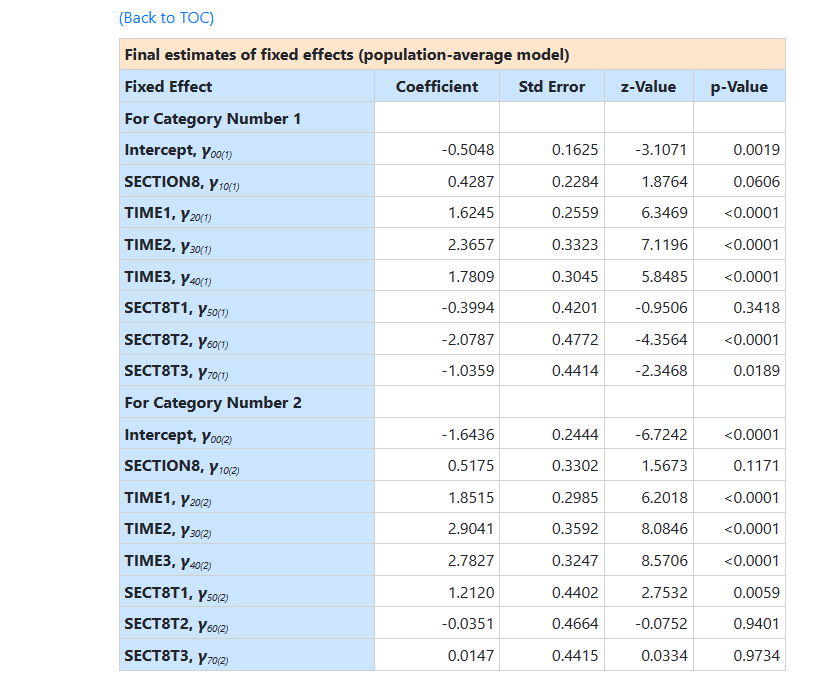

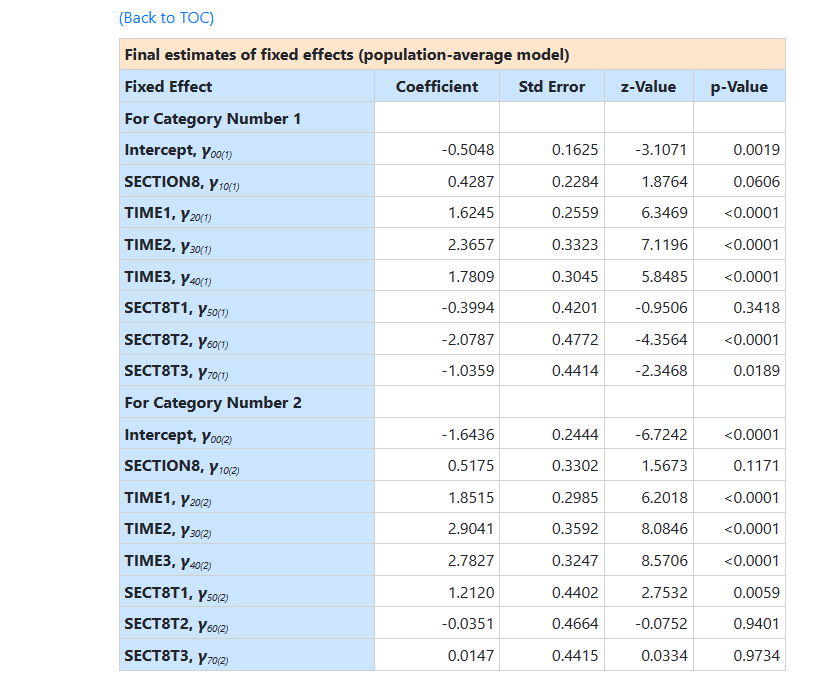

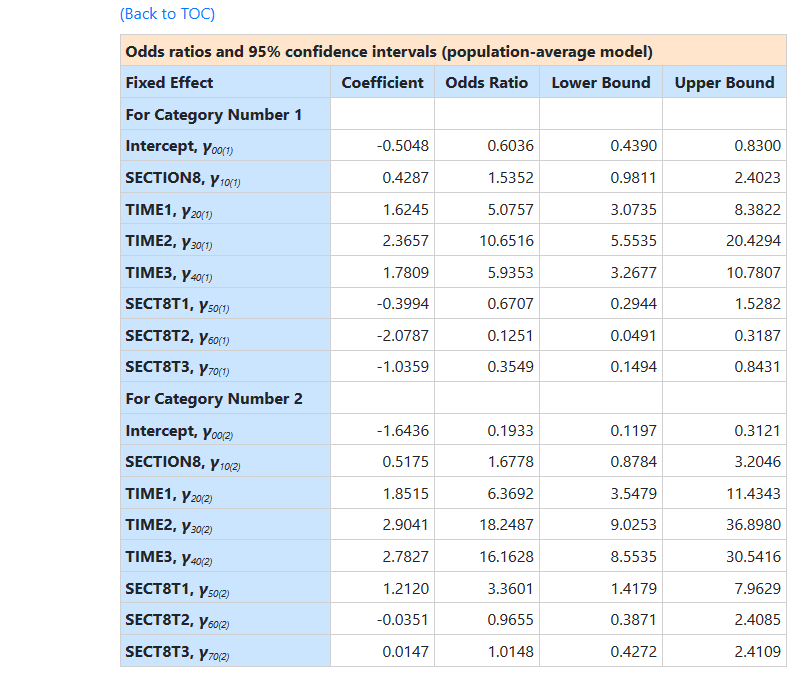

The output also includes the intracluster correlation coefficient for both categories, and population average results, as shown

below.

In terms of significance of the fixed effects, the time effects

are observed to be highly significant. With the inclusion of the Time by

Section 8 interaction terms, the time effects reflect

comparisons between time points for the control group (i.e., SECTION8

coded as 0). Thus, subjects in the control group show increased use of both

independent and community housing relative to street housing at all three

follow-ups, as compared to baseline. Similarly, due to the inclusion of the

interaction terms, the Section 8 effect is the group difference at baseline (i.e.,

when all time effects are 0). Using a .05 cutoff, there is no statistical

evidence of group differences at baseline. Turning to the interaction terms,

these indicate how the two groups differ in terms of comparisons between time

points. Compared to controls, the increase in community versus street housing

is less pronounced for section 8 subjects at 12 months (the estimate for

SECT8T2 equals –1.92 in terms of the logit), but not statistically

different at 6 months (SECT8T1) and only marginally

different at 24 months (SECT8T3). Conversely, as compared to controls, the increase in independent versus street

housing (response code 2 vs. code 0) is more pronounced for section 8 subjects at

6 months (the estimate equals 2.00 in terms of the logit), but not

statistically different at 12 or 24 months.

In terms of community versus street housing (i.e.,

response code 1 versus 0), there is an increase across time for the control

group relative to the Section 8 group. As the statistical test indicated, these

groups differ most at 12 months. For the independent versus street housing

comparison (i.e., response code 2 versus 0) there is a beneficial effect

of Section 8 certificates at 6 months. Thereafter, the non-significant

interaction terms indicate that the control group

catches up to some degree. Considering these results of the mixed-effects

analysis, it is seen that both groups reduce the degree of street housing but

do so in somewhat different ways. The control group subjects are shifted more

towards community housing, whereas Section 8 subjects are more quickly shifted

towards independent housing.

This differential effect of Section 8 certificates over time

is completely missed if one simply analyzes the outcome variable as a binary

indicator of street versus non-street housing (i.e., collapsing

community and independent housing categories). In this case (not shown), none

of the section 8 by time interaction terms are observed to be statistically

significant. Thus, analysis of the three-category nominal outcome is important in uncovering the beneficial

effect of Section 8 certificates.

The output also includes the intracluster correlation coefficient for both categories, and population average results, as shown

below.

References

Hedeker, D. & Gibbons, R.D. (2006). Longitudinal Data

Analysis. Wiley: New York.

Hedeker, D. & Gibbons, R.D. (1997). Application of random-effects pattern-mixture

models for missing data in longitudinal studies. Psychological Methods, 2(1):

64 – 78.

Hough, R.L., Harmon, S., Tarke, H., Yamashiro, S., Quinlivan,

R., Landau-Cox, P., Hurlburt, M.S., Wood, P.A., Milone, R., Renker, V.,

Crowell, A. & Morris, E., (1997). Supported independent housing:

Implementation issues and solutions in the San Diego McKinney Homeless

Demonstration Research Project. In W.R. Breakey & J.W. Thompson (eds.), Mentally

Ill and Homeless: Special Programs for Special Needs, pp. 95-117. New York:

Harwood Academic Publishers.

Hurlburt, M.S., Wood, P.A., & Hough, R.L. (1996).

Providing independent housing for the homeless mentally ill: a novel approach

to evaluating long-term longitudinal housing patterns, Journal of Community

Psychology, 24, 291-310.

where C represents the number of categories of the

outcome variable.

For the nominal model, the logistic link function is

specified.

In the current example, the outcome variable HOUSING

is coded 0, 1, and 2. Therefore

where C represents the number of categories of the

outcome variable.

For the nominal model, the logistic link function is

specified.

In the current example, the outcome variable HOUSING

is coded 0, 1, and 2. Therefore

As we wish to use the “street” category as

reference category, we select the first category as reference category and will

thus be considering the two logits

As we wish to use the “street” category as

reference category, we select the first category as reference category and will

thus be considering the two logits

For c = 2 (community housing)

For c = 2 (community housing)

and for c = 3

and for c = 3

.

The level-2 model is

.

The level-2 model is

thereby opening the Data page. Select the CSV file and click Open to

obtain the page below.

thereby opening the Data page. Select the CSV file and click Open to

obtain the page below.

The first step is to select an ID variable. In this case, the variable ID defines

the hierarchical structure, and we select it by checking the box associated

with this variable in the ID 2 line. To select predictors, the boxes in

the Variables line must be checked. We opt to select them all

The first step is to select an ID variable. In this case, the variable ID defines

the hierarchical structure, and we select it by checking the box associated

with this variable in the ID 2 line. To select predictors, the boxes in

the Variables line must be checked. We opt to select them all

before clicking Update. Once Update is clicked the program automatically

determines the appropriate levels of all selected variables.

before clicking Update. Once Update is clicked the program automatically

determines the appropriate levels of all selected variables.

With data specification now complete, model building can begin. Click on Models

at the top of the page to move to the Models page.

With data specification now complete, model building can begin. Click on Models

at the top of the page to move to the Models page.

The TIME variables are selected from the Level-1 Variables field by holding

down the Control button while clicking on the names. Next, drag them all

into the level-1 equation before releasing the mouse button. The following

level-1 model appears:

The TIME variables are selected from the Level-1 Variables field by holding

down the Control button while clicking on the names. Next, drag them all

into the level-1 equation before releasing the mouse button. The following

level-1 model appears:

Add the three SECTION8 variables (SECT8T1, SECT8T2 and SECT8T3) in the same way to

the level-1 equation. Then add the variable SECTION8 to the intercept equation

at level-2 to obtain the final model

Add the three SECTION8 variables (SECT8T1, SECT8T2 and SECT8T3) in the same way to

the level-1 equation. Then add the variable SECTION8 to the intercept equation

at level-2 to obtain the final model

As these settings are exactly what we intend to use, we need not make additional

changes here. We can proceed to run the analysis.

As these settings are exactly what we intend to use, we need not make additional

changes here. We can proceed to run the analysis.

One can Save the model information to a syntax file with file extension

MLCJSN for potential reuse. By default, the default file name assigned

corresponds to the file name of the data file. Using this option is optional,

however, and one can simply click the Run Syntax option to start the

analysis.

Portions of the output file are shown below. The first

part of the output file gives a description of the model specifications. This is followed by

descriptive statistics for all the variables included in the model. We note that the

most frequent response was in category 2, i.e. "Independent"

on the nominal outcome HOUSING, while 23% indicated

that they were living on the street (HOUSING = 0, the reference category here

represented by the indicator variable HOUSING3). The variable HOUSING1 represents the

respondents living in community housing.

Note that the order of the indicator variables for HOUSING is the opposite of the original coding of the variable: as we selected the

first category as reference category, the program automatically recodes it to

make the selected reference category the last category in the working data set.

One can Save the model information to a syntax file with file extension

MLCJSN for potential reuse. By default, the default file name assigned

corresponds to the file name of the data file. Using this option is optional,

however, and one can simply click the Run Syntax option to start the

analysis.

Portions of the output file are shown below. The first

part of the output file gives a description of the model specifications. This is followed by

descriptive statistics for all the variables included in the model. We note that the

most frequent response was in category 2, i.e. "Independent"

on the nominal outcome HOUSING, while 23% indicated

that they were living on the street (HOUSING = 0, the reference category here

represented by the indicator variable HOUSING3). The variable HOUSING1 represents the

respondents living in community housing.

Note that the order of the indicator variables for HOUSING is the opposite of the original coding of the variable: as we selected the

first category as reference category, the program automatically recodes it to

make the selected reference category the last category in the working data set.

Results for the model without any random effects are

given next. The first eight values are those for the intercept, SECTION8, TIME1,

…, SECT8T3 for response code 1 vs. code 0, the last eight are for the same predictors, but

for response code 2 vs. response code 0.

Results for the model without any random effects are

given next. The first eight values are those for the intercept, SECTION8, TIME1,

…, SECT8T3 for response code 1 vs. code 0, the last eight are for the same predictors, but

for response code 2 vs. response code 0.

The results obtained with adaptive quadrature estimation are given next.

The results obtained with adaptive quadrature estimation are given next.

Comparing the log-likelihood value from this analysis to one where there are

no random effects clearly supports inclusion of the random subject effect

(likelihood ratio

Comparing the log-likelihood value from this analysis to one where there are

no random effects clearly supports inclusion of the random subject effect

(likelihood ratio  ). Expressed as intraclass correlations

). Expressed as intraclass correlations

and

and  for community versus street and independent versus street, respectively. Thus, the subject

influence is much more pronounced in terms of distinguishing independent versus

street living, relative to community versus street living. This is borne out by

contrasting models with separate versus a common random-effect variance across

the two category contrasts (not shown) which yields a highly significant

likelihood ratio

for community versus street and independent versus street, respectively. Thus, the subject

influence is much more pronounced in terms of distinguishing independent versus

street living, relative to community versus street living. This is borne out by

contrasting models with separate versus a common random-effect variance across

the two category contrasts (not shown) which yields a highly significant

likelihood ratio  favoring the

model with separate variance terms.

The unit specific results follow.

favoring the

model with separate variance terms.

The unit specific results follow.

In terms of significance of the fixed effects, the time effects

are observed to be highly significant. With the inclusion of the Time by

Section 8 interaction terms, the time effects reflect

comparisons between time points for the control group (i.e., SECTION8

coded as 0). Thus, subjects in the control group show increased use of both

independent and community housing relative to street housing at all three

follow-ups, as compared to baseline. Similarly, due to the inclusion of the

interaction terms, the Section 8 effect is the group difference at baseline (i.e.,

when all time effects are 0). Using a .05 cutoff, there is no statistical

evidence of group differences at baseline. Turning to the interaction terms,

these indicate how the two groups differ in terms of comparisons between time

points. Compared to controls, the increase in community versus street housing

is less pronounced for section 8 subjects at 12 months (the estimate for

SECT8T2 equals –1.92 in terms of the logit), but not statistically

different at 6 months (SECT8T1) and only marginally

different at 24 months (SECT8T3). Conversely, as compared to controls, the increase in independent versus street

housing (response code 2 vs. code 0) is more pronounced for section 8 subjects at

6 months (the estimate equals 2.00 in terms of the logit), but not

statistically different at 12 or 24 months.

In terms of community versus street housing (i.e.,

response code 1 versus 0), there is an increase across time for the control

group relative to the Section 8 group. As the statistical test indicated, these

groups differ most at 12 months. For the independent versus street housing

comparison (i.e., response code 2 versus 0) there is a beneficial effect

of Section 8 certificates at 6 months. Thereafter, the non-significant

interaction terms indicate that the control group

catches up to some degree. Considering these results of the mixed-effects

analysis, it is seen that both groups reduce the degree of street housing but

do so in somewhat different ways. The control group subjects are shifted more

towards community housing, whereas Section 8 subjects are more quickly shifted

towards independent housing.

This differential effect of Section 8 certificates over time

is completely missed if one simply analyzes the outcome variable as a binary

indicator of street versus non-street housing (i.e., collapsing

community and independent housing categories). In this case (not shown), none

of the section 8 by time interaction terms are observed to be statistically

significant. Thus, analysis of the three-category nominal outcome is important in uncovering the beneficial

effect of Section 8 certificates.

The output also includes the intracluster correlation coefficient for both categories, and population average results, as shown

below.

In terms of significance of the fixed effects, the time effects

are observed to be highly significant. With the inclusion of the Time by

Section 8 interaction terms, the time effects reflect

comparisons between time points for the control group (i.e., SECTION8

coded as 0). Thus, subjects in the control group show increased use of both

independent and community housing relative to street housing at all three

follow-ups, as compared to baseline. Similarly, due to the inclusion of the

interaction terms, the Section 8 effect is the group difference at baseline (i.e.,

when all time effects are 0). Using a .05 cutoff, there is no statistical

evidence of group differences at baseline. Turning to the interaction terms,

these indicate how the two groups differ in terms of comparisons between time

points. Compared to controls, the increase in community versus street housing

is less pronounced for section 8 subjects at 12 months (the estimate for

SECT8T2 equals –1.92 in terms of the logit), but not statistically

different at 6 months (SECT8T1) and only marginally

different at 24 months (SECT8T3). Conversely, as compared to controls, the increase in independent versus street

housing (response code 2 vs. code 0) is more pronounced for section 8 subjects at

6 months (the estimate equals 2.00 in terms of the logit), but not

statistically different at 12 or 24 months.

In terms of community versus street housing (i.e.,

response code 1 versus 0), there is an increase across time for the control

group relative to the Section 8 group. As the statistical test indicated, these

groups differ most at 12 months. For the independent versus street housing

comparison (i.e., response code 2 versus 0) there is a beneficial effect

of Section 8 certificates at 6 months. Thereafter, the non-significant

interaction terms indicate that the control group

catches up to some degree. Considering these results of the mixed-effects

analysis, it is seen that both groups reduce the degree of street housing but

do so in somewhat different ways. The control group subjects are shifted more

towards community housing, whereas Section 8 subjects are more quickly shifted

towards independent housing.

This differential effect of Section 8 certificates over time

is completely missed if one simply analyzes the outcome variable as a binary

indicator of street versus non-street housing (i.e., collapsing

community and independent housing categories). In this case (not shown), none

of the section 8 by time interaction terms are observed to be statistically

significant. Thus, analysis of the three-category nominal outcome is important in uncovering the beneficial

effect of Section 8 certificates.

The output also includes the intracluster correlation coefficient for both categories, and population average results, as shown

below.

A bar chart of the variable HOUSING is given below. Housing status at

the beginning of the study was mostly independent or in community housing. As

we would like to compare these categories to the “street” category,

we will be using the first category of HOUSING as reference category in the

analysis to follow.

A bar chart of the variable HOUSING is given below. Housing status at

the beginning of the study was mostly independent or in community housing. As

we would like to compare these categories to the “street” category,

we will be using the first category of HOUSING as reference category in the

analysis to follow.

The observed sample sizes and response proportions by group are given in the table

below. These observed proportions indicate a general decrease in street living

and an increase in independent living across time for both groups. The increase

in independent housing, however, appears to occur sooner for the section 8

group relative to the control group. Regarding community living, across time

there is an increase for the control group and a decrease for the section 8

group.

Regarding missing data, further inspection of indicates that there is some attrition

across time; attrition rates of 19.4% and 12.7% are observed at the final time

point for the control and section 8 groups, respectively. In addition, one

subject provided no housing data at any of the four measurement time points.

Since estimation of model parameters is based on a full-likelihood approach,

missing data are assumed to be "ignorable" conditional on both the

explanatory variables and observed nominal responses (Laird, 1988). In

longitudinal studies, ignorable nonresponse falls under Rubin's (1976)

"missing at random" (MAR) assumption, in which the missingness

depends only on observed data. In what follows, since the focus is on

describing use of the nominal model, we will make the MAR assumption (e.g., a

mixed-effects pattern-mixture model as described in Hedeker & Gibbons

(1997)) could be used.

Observed sample sizes and response proportions by group

The observed sample sizes and response proportions by group are given in the table

below. These observed proportions indicate a general decrease in street living

and an increase in independent living across time for both groups. The increase

in independent housing, however, appears to occur sooner for the section 8

group relative to the control group. Regarding community living, across time

there is an increase for the control group and a decrease for the section 8

group.

Regarding missing data, further inspection of indicates that there is some attrition

across time; attrition rates of 19.4% and 12.7% are observed at the final time

point for the control and section 8 groups, respectively. In addition, one

subject provided no housing data at any of the four measurement time points.

Since estimation of model parameters is based on a full-likelihood approach,

missing data are assumed to be "ignorable" conditional on both the

explanatory variables and observed nominal responses (Laird, 1988). In

longitudinal studies, ignorable nonresponse falls under Rubin's (1976)

"missing at random" (MAR) assumption, in which the missingness

depends only on observed data. In what follows, since the focus is on

describing use of the nominal model, we will make the MAR assumption (e.g., a

mixed-effects pattern-mixture model as described in Hedeker & Gibbons

(1997)) could be used.

Observed sample sizes and response proportions by group

and

and  ,

where S = street, C = community, and

,

where S = street, C = community, and